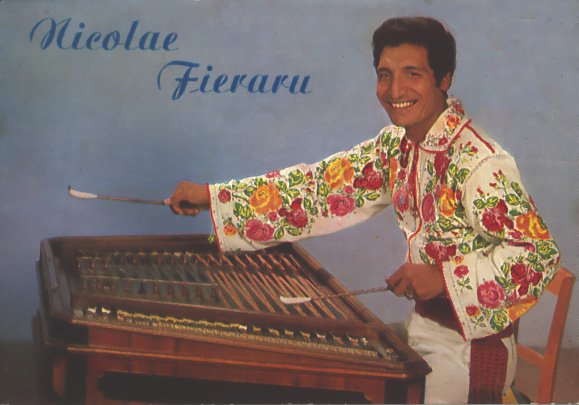

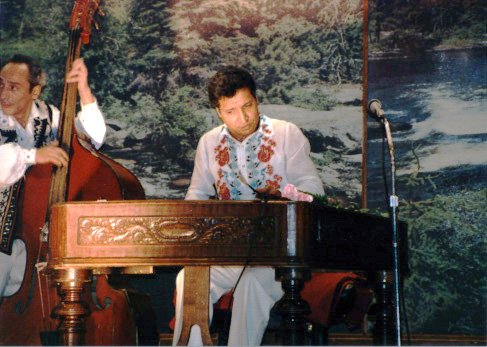

Biography

Sometimes when I talk to Americans or others about my music, it’s hard to know where to begin. So let’s start from scratch.

I am from Bucharest, the largest city in Romania, where I was born in 1950. Like my father and his father before him, I am a Gypsy and a musician. I play the cimbalom, a dulcimer in the Romanian tradition, called ţambal in Romanian. But I need to explain more.

For centuries, Gypsies in this part of Romania distinguish themselves from others by the occupations they follow. Some are nomadic, but most live in villages and cities, traditionally in their own neighborhoods. The many occupations they traditionally follow include those of coppersmith, flower seller, silversmith, spoon maker, and many others. I am a lăutar, a musician.

My grandfather, Marin Feraru, played the clarinet and also the small cimbalom (ţambal mic). He lived in Caracal, west of Bucharest. Around 1930 he moved to the city of Galați, on the Black Sea. My father, Ion Feraru, who played the ţambal mic and the cobza (a lute), settled at that time in Domneşti and later Chiajna, on the outskirts of Bucharest. He married my mother, who came from a lǎutar family from Baneasă, where the airport is now. Her father died in World War I, but members of her family played the violin and traveled long distances to play at weddings. My father and mother raised a family of seven children, and I am the second youngest.

In those years, my father played mostly in small taverns on the outskirts of Bucharest. Weddings and funerals, of course, were the main events where lăutari played. Before Communism, village weddings lasted four or five days, sometimes involving two groups of musicians. Work for musicians was relatively good. However, once the land was collectivized, around 1962, peasants were obligated to work in the fields and animals were no longer private property. They now had to work on the weekdays and had less meat to share, so weddings now lasted only two days, Saturday and Sunday. Lăutari were now less in demand. The wedding party now took place at the house of the godparents on Saturday, and the music began at 8 or 9 a.m. on Sunday at the bride’s family’s house. It carried over into Monday at the groom’s family’s house or at the house of anyone in the village. However, lăutari weddings take place on Tuesdays or Thursdays (so that they can be available on weekends) and flower-seller weddings on Mondays.

In the late 1950s, my father played and sang in a taraf led by Costică Cobzaru. This group consisted of two violins, accordion, ţambal mic, and bass. They performed cîntece batrîneşte (ballads, “old folks’ songs“), maybe as many as twenty, while the wedding party ate dinner. Then dancing began, followed by more food and listening music, and then dancing again. I remember lots of family dinners on Mondays where my father simply fell asleep—he had been up all night at the wedding and then had to go to work on Monday as a chimney sweep. He told me again and again not to become a lǎutar.

But I liked to play his ţambal mic and by the time I was eleven I was playing it in wedding processions with him. We had little money and I would have to wear my mother’s shoes on those occasions. At that time (the early 1960s) the cimbalom had been somewhat in decline. Apart from Ciuciu, in Bucharest there were only a few players, like Nicolae Vişan and Nicolae Bob Stănescu. But Toni Iordache, then in his teens, was starting to play at weddings, and after hearing his playing at one, I idolized him. My father arranged for me to get lessons on the big cimbalom with Toni’s teacher, Miticǎ Marinescu-Ciuciu.

Ciuciu was from a family of cimbalom players, born in 1913 in the village of Ileana, outside Bucharest. He played the concert (Hungarian) cimbalom, not the small “Romanian” instrument that my father and I played. Before World War II, he had played with the famous violinist Grigoraş Dinicu and others. He played regularly with all the traditional orchestra leaders of the day, like Ionel Budişteanu, Nicu Stănescu, Nicuşor and Victor Predescu, as well as singers like Maria Tănase and Maria Lătareţu. He could read music and toured as far as Japan and Canada. He was generous and soon took a fatherly interest in me. My father bought a large cimbalom and, because the tuning was different from the small one I had played on up to that time, I had to start from scratch. Mainly he taught by ear, although I also learned to read music as well as the elements of theory and harmony from him. He would play part of a tune, then I would copy him, and he would continue with more of it, until I had it down. But, after a couple of months of lessons for which my father paid, Ciuciu made me part of the family. I lived at his house much of the time, went with him to concerts and weddings where he played, and I absorbed everything I could at those places. During my school years, I also played in the orchestra at the local “house of culture” and played the harmonica in school.

In the Communist system, if you were going to make a living with music, you had to be tested every four or five years and, based on your training, you were placed in one of three (later five) categories, corresponding to how Romanians thought of musicians: muzician, muzicant, and lăutar. The highest rank was muzician. If you knew theory, could sight read something the jury placed before you, and could play a variety of music, they might award you this rank. The lowest rank might be given to someone who was a traditional musician, unable to read music, and knowledgeable only in the traditions of his village. Each rank determined your pay and where you could play. I received the top rank and became a “free professional,” meaning that I could seek work in restaurants or anywhere else that might want to hire me and also could tour abroad.

In 1969, I auditioned for a spot as a musician at the Teatrul “Ion Vasilescu” in Bucharest. This was my first professional job. Then I went into the Army for a year and a half and was part of an ensemble. Sometimes I played for official receptions with Toni Iordache (who at the time played in an ensemble sponsored by the Ministry of the Interior) during this period.

After I got out of the Army, I played with the panflutist Radu Simion in his ensemble at the Caru’ cu Bere restaurant for about a year. In 1972, I married Lelia Scarlat, the daughter of a lăutar from Urziceni. That year I went on tour to the United States and Canada, playing before Romanian communities, as part of an ensemble accompanying the famous singer Gica Petrescu. In 1973, I played for four months at a restaurant on the Île d’Orleans near Montreal, with Tudor Dobre and a Hungarian violinist, Lajos Molnar. Those were great opportunities and I was tempted to leave Romania for the West then, but I returned.

I played at the Caru’ cu Bere with the violinist Nicu Pătraşcu, and then had a job in 1974 for about a year with a song-and-dance ensemble, “Doina Ilfovului.” I then began an association with Radu Simion that lasted until I left Romania. We played regularly at various Bucharest restaurants, including the Crama Domneasca, theHora, the Hunedoara, and the Olimp. Gheorghe Zamfir had created a craze for the panpipes in Western Europe, especially Switzerland, France, and Holland, and Radu’s group traveled to those countries several times in the late ’70s and early ’80s. In Holland, we played for the royal family and we stayed there long enough for me to give lessons to several students. In Bern, Switzerland, we played at a United Nations-sponsored concert that featured the Bolshoi Ballet. We earned very good money, and I was able to buy a Hungarian-made Bohák cimbalom in Switzerland, something that was virtually impossible to get in Romania.

I made a couple of solo records for the Electrecord label (in 1975 and 1984) and appeared on others. The company, of course, produced the records, but some of the crazier aspects of Communist-era record production need to be told. We first we would go into the studio and record around twenty pieces. Then a committee, which would likely consist of Tiberiu Alexandru (Romania’s leading ethnomusicologist), a director of a radio station, a party bureaucrat, and a representative of the composers’ union, would audition the tape and decide what would make the final cut. I suppose they would base their decisions partly on what they thought sounded the best, but some of their decisions were grounded in political ideology. When it came to muzică lăutarească (Gypsy music), they became critical. For example, the committee rejected the recording we made of Nici nu ninge, apparently because in its traditional style, using the triple rhythm, it sounded too “Gypsy.” So we recorded it again, this time changing it to a free-rhythm doină, and it satisfied the committee.

In the 1980s things got worse and worse in Romania, both politically and economically. Personally I never had problems getting food, since I worked at restaurants and had enough money anyway. But politics were getting out of control. It was bad enough that every orchestra had to provide a program list to an inspector, to show that they would only play appropriate music (meaning that muzică lăutarească especially had to be very limited). After all, if the inspector happened to hear you play something he didn’t like, you could buy him off with a bottle of wine. What was worse was the presence of miniature microphones placed in ashtrays on the tables. And forget about talking to foreigners. Add to this the need to stop nightlife at nine o’clock, in order to save electricity, and you had a very grim place.

One of the most bizarre indignities I had to suffer was when I was edited out of a television performance. The official policy was never to identify the traditional music we played as “Gypsy” music, even though all cimbalom players in Romania were Gypsies. My features are such that I can’t be mistaken for anything else, so the television editors taped an actor playing a cimbalom. They kept the sound, but spliced in the actor when they wanted to show me.

So, when an opportunity presented itself in 1988 to go on a tour to the United States and Canada, I made plans to leave for good. Things had been getting worse for several years, without hope of ever improving, and opportunities to tour were becoming scarce. Under the name “Rapsodia Carpaţilor,” Ion Lǎceanu, a singer and player of the fluer, caval, bagpipes, and fish scale, hired me and four other musicians. We were to accompany dance ensemble and singers. I paid the expensive transportation fee on my cimbalom and we flew to Detroit, which was to be our base for the North American tour.

After playing for Romanian communities all over the United States and Canada, we returned to Detroit. But when it was time to fly back, I stayed, along with one other musician and nearly all the dancers! Nobody mentioned the topic while we were together, although Lăceanu said later that he suspected all along that I didn’t plan to return. In fact, in Romania I told only my mother-in-law of my plans. If my children were to know, they would pose a big risk that word would get out. We just couldn’t talk freely in those days.

The Romanian immigrants and Romanian-Americans that we met made the transition to a new life easier. In fact, many had left by swimming across the Danube and now were in comfortable circumstances, employed in industrial jobs. They were sympathetic and helpful. I applied for political asylum, learned to drive a car, and started to learn English all at the same time. I got an apartment in Detroit and got a job working for Bill Webster making dulcimers.

I met Pavel Cebzan, a great clarinetist from Timişoara who had toured with Zamfir and, after coming to the U.S. to tour with singer Nicoletă Voica, also stayed inDetroit and applied for asylum. For the next year I played with them regularly at Descent of the Holy Ghost church in Warren, Michigan, to large crowds of enthusiastic immigrant Romanians. I also played at the old Hungarian Village Restaurant. Those were exciting years, as we witnessed big political changes. I was fortunate to have taken part at some events that would have been unthinkable a few years earlier. For example, in 1991 I played as part of a tour which featured a performance of an ensemble from the independent republic of Moldova, “Lăutarii,” led by Nicolae Botgros, and in Chicago I played with them with former King Michael in the audience.

But my wife and five children were still in Bucharest. I moved to Chicago in 1993 and in addition to playing for various affairs, got a job in a factory. I brought over my wife Lelia and sons Laurenţiu, Jan, and Bogdan, in 1994. My daughters Janina and Fǎnica had to stay behind. I continued to play for various affairs, mostly in the Romanian community, but also many others.

I play solo, in the virtuosic Romanian style popularized by the late Toni Iordache, as well as accompaniment on the cimbalom. I specialize in a Romanian repertoire, including Gypsy music (muzică lăutarească), regional styles, as well as café concert and international pieces. I learned all this music from the people I described above. Let me know if you would like me to be a part of your celebration.